Next Lesson - Introduction to Autoimmunity

Abstract

- Allergy is a hypersensitivity reaction to an allergen which can be IgE or non-IgE mediated.

- Food allergies are common and account for a significant disease burden with varying prevalence across ages depending on the allergen.

- Diagnosis of food allergy requires a focused history, examination and investigations, including skin prick test (SPT), blood tests and oral food challenge (OFC) as the gold standard.

- Management of food allergy relies heavily on the patients themselves and in case of severe reaction, they should be educated on how to self-administer adrenaline using an adrenaline autoinjector such as an EpiPen®.

Core

Allergy is defined as a hypersensitive reaction which can be IgE mediated (e.g. peanut allergy) or non-IgE mediated (e.g. milk allergy) in response to antigens present on extrinsic allergens.

Major allergic disorders include hay fever (or allergic rhinitis), allergic conjunctivitis, asthma, eczema, urticaria, and insect, drug and food allergies.

Allergen is the term used to describe the protein or cellular component triggering the allergic reaction.

Atopy is the term used to describe the genetic tendency to produce IgE antibodies in response to exposure to substances that usually prompt no reaction. This means these people are more likely to develop allergic diseases such as asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis.

Anaphylaxis is the most severe form of allergy. It is a life-threatening response to an allergen where there is narrowing of the airways and a drop in blood pressure resulting in shock. Without treatment, anaphylaxis will rapidly progress to death.

Sensitisation is the term used to describe the production of IgE antibodies following a first exposure to an allergen, which results in the production of a reaction on the second and subsequent exposures that does not occur on the first exposure. Certain allergic conditions are more prevalent in children than adults (e.g. food allergy, eczema) as the reaction lessens over time with repeated exposures, whereas others are more common in adulthood (e.g. rhinitis) as repeated exposure results in increased sensitisation and more severe reactions.

Food intolerance is when the body produces an adverse response to a food type, but which does not involve the immune system (e.g. indigestion). These can be caused due to metabolic abnormalities (e.g. the missing lactase enzyme in lactose intolerance) or psychological effects (e.g. aversion to certain foods).

A food allergy is when exposure to a food type triggers a hypersensitivity reaction which can be IgE (immediate onset) or non-IgE (delayed onset) mediated.

There are two types of presentation depending on the underlying molecular mediators of the reaction:

Immediate Onset Presentation – IgE mediated and accounts for 40% of cases. Typical symptoms manifest through the skin, respiratory system, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract (e.g. urticaria, cough, wheezing, vomiting and diarrhoea). In severe cases, it can be life-threatening and cause anaphylaxis.

Delayed Onset Presentation – non-IgE mediated and accounts for 60% of cases. Typical symptoms predominantly affect the GI tract and thus can be more difficult to diagnose as symptoms can be quite non-specific. This can include diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, and bloating.

Examples

There are 14 common allergens that are listed by the UK Food Standards Agency. In the United Kingdom, it is a requirement that all food businesses provide information about the allergenic content of their food.

The fourteen allergens on the list are celery, cereals with gluten, crustaceans, eggs, fish, lupin (found in flour), molluscs, mustard, nuts, peanuts, sesame seeds, soya, and sulphur dioxide (found in dried fruits).

Many of the above foods contain allergens that are heat sensitive. This means that during the cooking process, the allergenic protein is denatured, meaning that it no longer causes the reaction. This can also be applied to the canning process as this involves heating the food. This is why some people with allergies cannot have raw celery but can have cooked celery in a pre-prepared sauce or cannot have freshly cooked fish but can have tinned fish.

Diagnosis of food allergy is usually made following a stepwise approach. The first step is to elicit key elements when taking the clinical history:

- Context of the Reaction – age of onset, route of exposure, and intercurrent illness

- Presenting Symptoms – timing of onset, severity, and duration. Particular questions should be asked about breathlessness, itching and gastrointestinal upset as these are common initial presenting features

- Foods Ingested – new, cooked, quantity, and previous reactions

- History – any personal or family history of atopic conditions, including asthma, eczema, hayfever and other allergies

Next, one should carry out a thorough physical examination to identify the clinical manifestation of the allergic reaction and develop a differential diagnosis. This involves looking across the whole skin for rashes and examining the throat and mouth. Physical examination should also, in addition to history taking, be an opportunity to look for any stigmata of other allergic conditions such as eczema.

If the suspicion of food allergy persists, screening tests are carried out. These involve the skin prick technique where a small amount of allergen is introduced under the skin with a needle and observed for a reaction (which looks for mast cell activation) and blood tests screening for the presence of IgE antibodies.

The next intervention involves a trial of an elimination diet avoiding the suspected allergen. If the suspected allergen is the cause, this will improve symptoms. If the removal of the suspected allergen does not resolve the symptoms, check for accidental exposure and consider other potential allergens.

In some cases, it might be useful to assess cross-reactivity with other foods where allergy to a certain food can increase the risk of allergy to others sharing similar proteins. This can be done using the oral food challenge (OFC) where the suspected similar allergen is administered in a monitored and standardised setting to identify the level of responsiveness or tolerability and helps confirm any diagnosis of allergy. This is the gold standard, except where contra-indicated, i.e. where there is a history of previous anaphylactic reaction.

After a confirmed diagnosis of food allergy, management to prevent allergic reactions is very much patient-centred and requires great patient awareness and education to enable them to adapt their lifestyle in an appropriate way. Patients need to be taught about the main foods to avoid and about how to read allergen warning labels on food packaging, which in the United Kingdom are highlighted in bold on the ingredients list. Depending on the severity of the allergy some patients are advised to avoid even potential traces of foods contained in packaged goods.

While restricting the diet to avoid the allergen can be advisable in cases of severe allergy, it is important to ensure that a balanced diet is still achieved. This means that referral to dieticians can be useful for those with multiple or severe allergies.

In cases where the allergic reaction is not mediated by IgE antibodies, food reintroduction can be an option. Lactose intolerance is a good example of this. Lactase is the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of lactose into galactose and glucose. It is found in the jejunal brush border (the wall of the small intestine) and has a peak concentration in a newborn. Lactose intolerance is caused by the non-persistence of the lactase enzyme (meaning the levels of lactase produced gradually decline), which results in symptoms of bloating, flatulence, and explosive diarrhoea. The onset can be quite subtle and progressive, usually diagnosed in adolescence or adulthood.

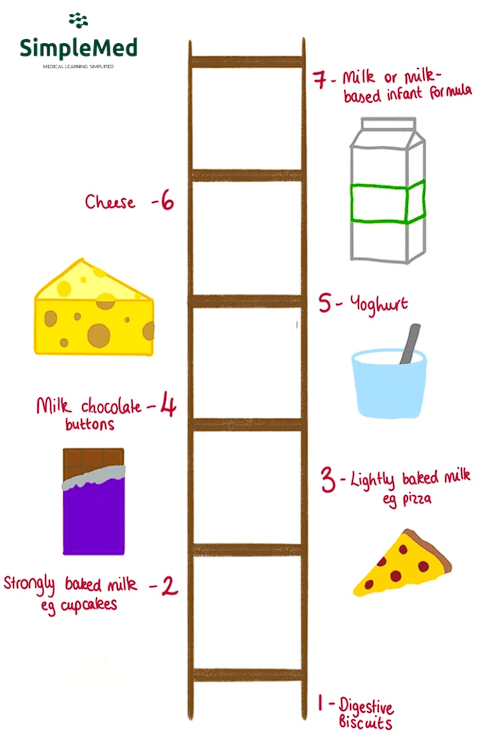

Reintroduction is usually done progressively using the so-called milk ladder, starting with products containing more denatured proteins (hence, less allergenic) and stepping up to less denatured ones as tolerance is restored. The ladder usually follows a similar path to this: cookie or biscuit with milk as an ingredient (baked) -> cake or pancake with milk (milk is a more core ingredient here but it’s still baked) -> lightly baked milk (e.g. cheese on a pizza) -> chocolate -> yoghurt (fermented) -> cheese (pasteurised) -> milk.

Diagram - Visual representation of the milk ladder

SimpleMed Original by Dr. Maddie Swannack

Some severe forms of allergic reactions can lead to anaphylaxis. This is a life-threatening situation and should be treated as an emergency.

It happens when mast cells release a large amount of histamine which leads to vasodilation and bronchoconstriction resulting in a drop in blood pressure and narrowed airways. Patients should be aware of these red flags (tachycardia, sudden drop in blood pressure, increased warmth of the extremities and difficulty breathing) and trained in the use of an adrenaline autoinjector (such as an EpiPen®), which is a device for auto-injection of adrenaline in case of anaphylaxis. Correct use of such a device can be lifesaving.

Patients should also be issued with an allergy action plan for instructions on what to do in case of anaphylaxis. Rapid administration of adrenaline is the first line treatment and not using an adrenaline auto-injector when needed does more harm than doing so when not indicated so when in doubt, it is best to use the adrenaline auto-injector and call for help.

It is important to remember that the half-life of adrenaline in the body is short, so while an adrenaline auto-injector can be lifesaving, the effects will not last that long. This is why is it very important to call for help as soon as the adrenaline is given, so ongoing management can be put into place. Patient and family/carer education around this is essential.

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 1706