Next Lesson - The Immunocompromised Host

Abstract

- In 2017, the estimated number of people living with HIV was of about 36.9 million, around 25% of them not being aware they have the virus.

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus is a single stranded enveloped virus, it replicates using the host’s machinery back into DNA and ssRNA again. It infects cells with CD4+ surface receptors.

- Treatment currently involves a combination of anti-retroviral drugs that target different stages of the HIV infection and replication processes in order to try and slow the progression of the disease.

- Important efforts to tackle the spread of the disease focus on prevention of transmission, but stigma is currently one of the main barriers to potential elimination of the disease.

Core

Globally, HIV is a major public health concern and has proven to be a great challenge since it was first identified in the early 1980s. Despite an estimated decrease in incidence (new cases), prevalence (total cases) of HIV is increasing worldwide as life expectancy with the disease has increased with new treatments. To illustrate the scale of the disease, it is believed that 36. million people were living with HIV in 2016, of which 1.8 million were new cases and only 75% of people were aware of their status (source).

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a retrovirus that belongs to the Retroviridae family, Lentivirus genus.

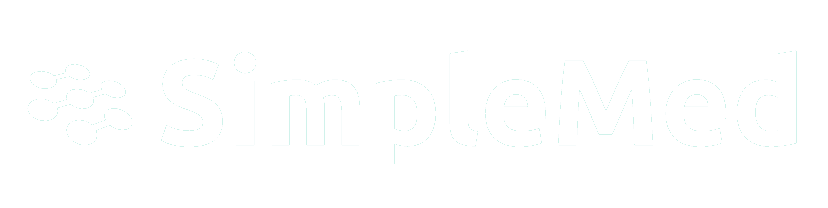

HIV specifically affects cells of the immune system specifically CD4 cells (a type of white blood cells). After hijacking the cell’s machinery in order to replicate the cells are destroyed. Extent of the infection is estimated by the patient’s CD4 T-cell count. A normal range of CD4 T-cell count would be between 500 and 2000 cells/μL. HIV progression can be divided into 4 different progressive stages with regards to this parameter:

- Stage I corresponds to a ‘normal’ CD4 count >500 cells/μL and the patient is usually asymptomatic;

- Stage II is when the count <500 cells/μL and the patient starts to show mild symptoms;

- Stage III is described as a CD4 count <350 cells/μL and symptoms start to become more advanced;

- Stage IV is when the CD4 count <200 cells/μL and the presentation is more severe, also defined as AIDS.

- Seroconversion: this stage is characterised by acute HIV syndrome with symptoms: fever, malaise, weight loss and generalised rash. This is seen on the image below where the CD4+ count initially drops on initial infection and copies of the HIV virus spike in number. This acute stage can easily be mistaken for glandular fever which has a similar presentation. Therefore, as HIV can be contracted by anyone it should be considered as a differential diagnosis and simple testing should be carried out to rule out the condition.

- Latent stage- CD4+ numbers slowly drop, and viral load slowly increases but the disease is clinically silent. HIV associated infections may begin to develop in the late stages.

- AIDS- when CD4+ count drops below 200 cells/μL and opportunistic infections begin to take hold.

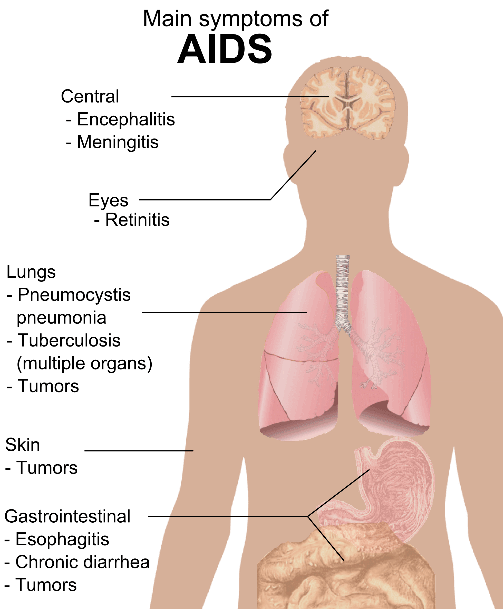

AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is the term used to describe the most advanced stage of HIV infection when the patient has become ‘immunodeficient’ (or fully immunocompromised). The patient is now susceptible to serious complications from previously harmless infections, opportunistic pathogens (organisms that are not usually pathogenic in those with normal immune systems) and malignancies. A few examples include: HHV8- a virus which is the cause of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a diagnostic infection for AIDS; Pneumocystis pneumonia, candidiasis, protozoal infections. Death is not caused by the HIV virus itself but through conditions like these.

Figure: Shows the changes in CD4 lymphocyte count over time in a patient with HIV

Creative commons source by Jurema Oliveira [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

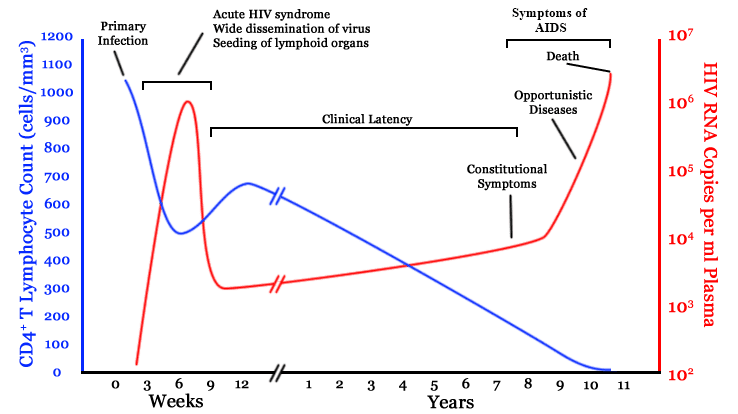

There is no specific physical sign relating to HIV infection itself, but signs related to worsening immunosuppression can be observed at different stages of infection. There is no specific physical sign relating to HIV infection itself, but these rather start presenting as a result of the immunodeficiency caused by progression of the infection. Acute seroconversion can manifest with flu-like symptoms as described above. As CD4+ cell count drops, recurrent and severe infections e.g. oral candidiasis, begin to present. The first signs of HIV-related illness usually develop within 5 to 10 years, or sometimes even less. Progression of the disease overall and in turn onset of HIV related disease and onset of AIDS depends on the level at which the virus is cleared to (amount of viral load) after seroconversion and the host’s existing immune system.

Figure: The main signs and symptoms of an Acute HIV infection

Creative commons source by Mikael Häggström [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

Figure: The main signs and symptoms of an AIDS infection

Creative commons source by Mikael Häggström [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

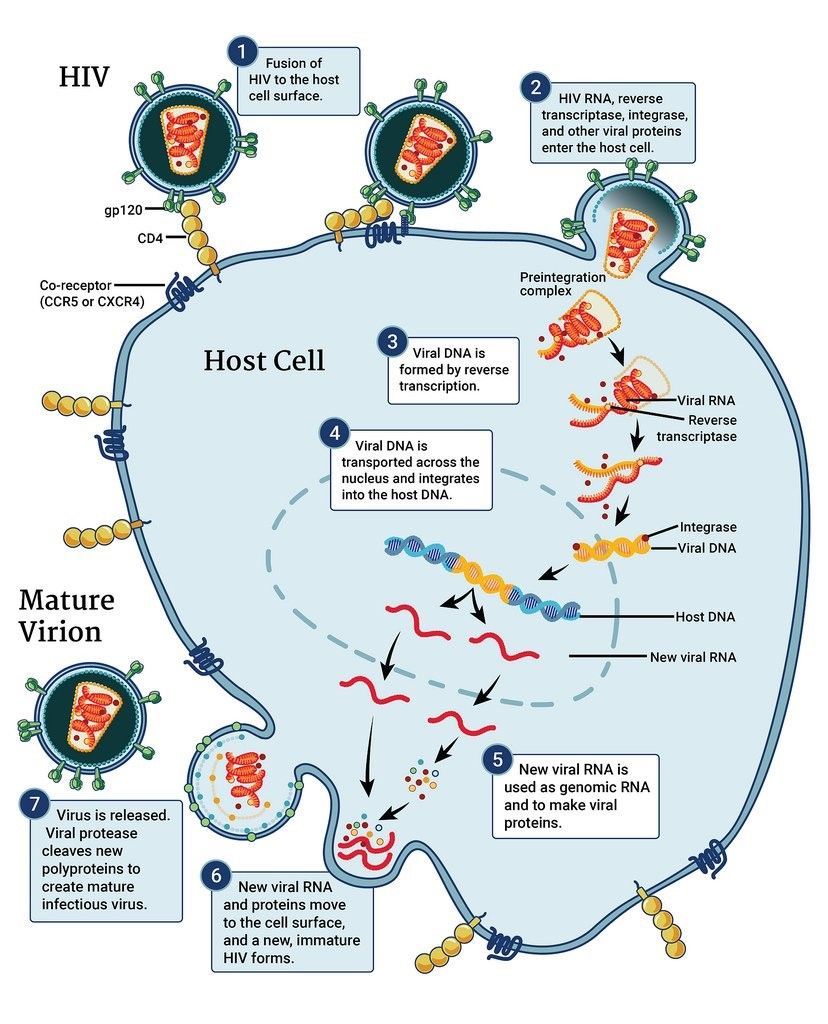

The Life Cycle of HIV and Drug Targets

There are 7 steps of the HIV life cycle (i.e. how it hijacks and replicates in CD4 T-cell). These are important to understand as they are used as targets for treatment:

- Binding (or Attachment) – HIV binds to the receptors on the surface of the CD4 cell (either CCR5 or CXCR4). CCR5 antagonists/post-attachment inhibitors act here.

- Fusion – the viral envelope then fuses with the CD4+ cell membrane which allows the virus to penetrate the cell by emptying its contents inside the CD4+ host. These contents include HIV RNA and the reverse transcriptase enzyme. Fusion inhibitors act here.

- Reverse transcription – inside the CD4+ cell, reverse transcriptase converts the HIV RNA into HIV DNA, which then enters the CD4+ cell nucleus. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)/nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) act here.

- Integration – inside the nucleus, HIV integrases permanently combine the viral DNA with the CD4+ cell’s own DNA. Integrase inhibitors act here.

- Replication (or Transcription) – when the infected cell divides, the DNA is ‘read’, and long chains of viral protein are made.

- Assembly – the new HIV proteins and RNA move to the surface of the cell and assemble into ‘immature’ (non-infectious) HIV.

- Budding – newly formed immature HIV pushes itself out of the host CD4+ cell. The new HIV cell releases proteases which break up the long ‘immature’ protein chains into smaller ‘mature’ (infectious) HIV. Proteases inhibitors (PIs) act here.

Figure: The Life Cycle of HIV

Creative commons source by NIAID [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

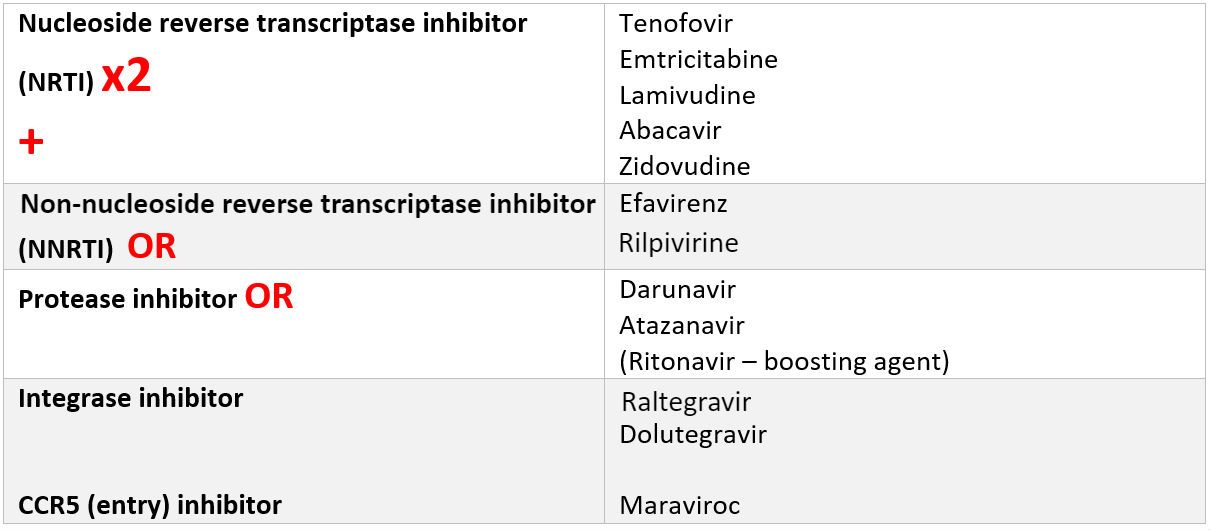

As you can imagine, a lot of these HIV-specific enzymes are potential drug targets and by targeting different stages of the HIV life cycle simultaneously, the efficacy of treatment overall, avoiding the threat of resistance. This is why current treatment involves what is called ‘combined’ therapy: patients are prescribed a combination of 3 anti-retrovirals (ARVs) - known as triple drug therapy or highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (if you are particularly interested in this topic it is worth visiting this webpage):

Figure: Drugs used to treat HIV

SimpleMed original by Elena Perez

Whatever the particular drug regimen someone is given, they will have to take the combination of medicines every day. It is important to point out that currently, treatment is not curative but will increase life expectancy (slowing or halting progression) and prevent the spread of HIV by reducing the risk of transmission.

As we have just seen (despite a unique success story), there is currently no cure for HIV. Although treatment is helpful in allowing patients to have a near normal life expectancy and quality of life, it is also very expensive and as a result only a small portion of patients are being treated worldwide. Thus, important efforts are being placed in prevention.

These are some of WHO’s recommendations to help limit the risk of HIV transmission through sex:

- The correct use of male or female condoms for every sexual intercourse

- Taking antiretroviral drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV (PrEP)

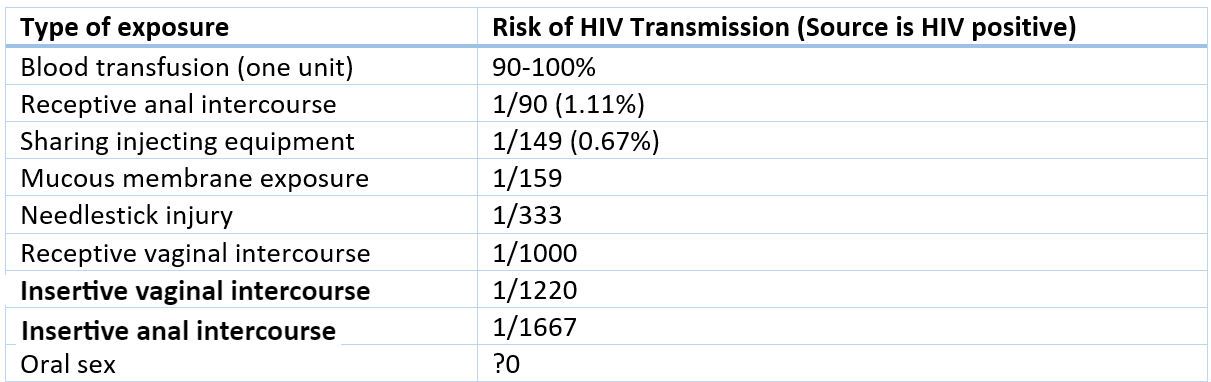

Being a blood borne virus, sexual contact is one mode of transmission - but not the only one. Any contact of infected bodily fluids with mucosal tissue, blood or broken skin can be a route of transmission. Therefore, apart from sexual contact (that accounts for 95% of infections), HIV can also be transmitted through medical procedures such as blood transfusions, contaminated needles (mainly through needle exchange among IV drug users), or perinatal transmission (vertical transmission).

Not all these modes of transmission have an equal risk. There are certain factors that affect the risk of transmission: the type of exposure (type of sexual act/transfusion/needlestick (see article on hepatitis)/mucous membrane), the viral load in blood (if the viral load was undetectable in the first place, transmission is highly unlikely), etc.

Figure: Shows the risk of HIV transmission depending on the type of exposure

SimpleMed original by Elena Perez

HIV Testing and Ethical Dilemmas

The earlier HIV is diagnosed, the better the prognosis as the higher CD4+ count can be maintained. Therefore anyone who suspects they might have become infected should attend their occupational health clinic or sexual health clinic for testing as soon as possible.

There are a few different tests that are used:

- Rapid Test (Point of Care (POC) test) – low cost, rapid test that can be done at home as a discreet postal test and involves either blood testing through a finger-prick or saliva (taken as an oral swab). The test produces very few false negatives so if negative it is most likely an accurate result. The test dos however produce false positives, so if positive, the results needs to be confirmed with further serology testing.

- Serology – involves a full blood sample sent off to a labs with much slower results (within 7-10 days). This test looks for HIV antigen (viral protein) and HIV antibody (immune response to the antigen). It is slightly more accurate but might result in a false negative result.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) – detects HIV nucleic acid. It is a highly sensitive test which can detect very early infection (few days) but it is expensive, and results can take up to a week. This is not used for initial HIV testing but for follow-up and monitoring treatment response.

Who should be tested? Current guidelines state that anyone presenting with the following should be tested:

- Everyone in a population with an incidence rate > 2/1000

- Bacterial pneumonia/TB [Resp]

- Meningitis/dementia [Neuro]

- Severe psoriasis; recurrent/multidermal shingles [Derm]

- Chronic diarrhoea/weight loss with unknown cause [Gastro]

- Any unexplained blood abnormality [Haem]

- Lymphoma, anal cancer [Onc]

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [Gynae]

- Any STI/HepB/HepC

In some cases, some patients (let’s say a nurse who undergoes a needlestick injury) might opt in to have post-exposure prophylaxis treatment given immediately to increase the chances of preventing infection. This is only given in certain emergency situations that need to meet the guidelines and must be started within 72 hours after the possible exposure to HIV.

Because of the infectious nature of HIV, there are some ethical dilemmas healthcare professionals might face. Ideally, testing should be done with consent from the patient who should be then trusted to disclose their status with their partner(s) or anyone they might put at risk of infection. However, in some situations, we might be asked for example, as GPs, not to tell a patients’ partner. The ethical dilemma here rests on patient confidentiality vs harm to the general public. It would be best advised in this case to make sure to talk the patient through the importance of the disclosure of such information as and explain the dilemma weighing patient confidentiality against other people’s safety (i.e. the health of a mother, an unborn child, a sexual partner etc.).

Another important aspect of HIV is the stigma that still can be associated with the condition. When making a diagnosis of HIV, healthcare professionals must be aware of the impact this might have on their patients and provide them with the right support, medically but also psychologically.

Edited by: Dr. Ben Appleby and Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 7397