Next Lesson - Asthma

Abstract

- A pulmonary embolus (PE) is most commonly a thromboembolism that began as a deep vein thrombosis, has travelled through the right side of the heart, and has become lodged in an area of pulmonary vasculature.

- Risk factors for a PE include pregnancy, prolonged immobilisation, the combined oral contraceptive pill, and obesity.

- A PE causes right ventricular strain, pulmonary vasoconstriction, and type 1 respiratory failure.

- Symptoms of a PE include dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, and a cough, whilst signs include dyspnoea, tachycardia, low BP, and a raised jugular venous pressure.

- Investigations for PE include arterial blood gas, chest x-ray, d-dimers, and an ECG.

- Patients who have had a previous PE should be put on an oral anticoagulant.

Core

An embolus can be defined as the movement of a material from one part of the circulation to another. An embolus will usually travel until it reaches a part of the circulation that is too small for it to pass through, at which point it will block that part of the circulation and cause pathology.

A pulmonary embolism (PE) is therefore material that has moved from one part of the vasculature, through the right side of the heart, and lodges in the pulmonary arteries.

An embolus is usually made from a blood clot (thromboembolism), but can also be formed from tumour, air, fat, or amniotic fluid – note that the rest of this article will be focussing on thromboemboli. Pulmonary emboli are the third most common cause of vascular death, after myocardial infarction and stroke, and are the most common cause of preventable death in hospital patients.

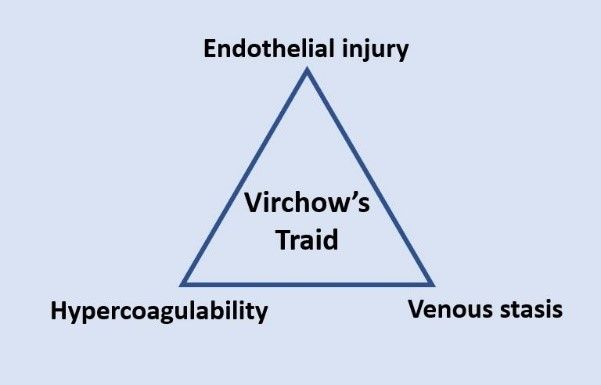

90% of PEs arise from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a thrombus that has formed in the deep veins of the lower limb. The main factors that contribute to thrombus formation are stasis of blood flow, hypercoagulability of blood, and endothelial injury, also known as Virchow’s Triad. This means that the risk factors for a DVT (and therefore PE) are factors that will contribute to the causation of part of this triad:

- Pregnancy

- Prolonged immobilisation (e.g. post-operatively or on a long-haul flight)

- Previous venous thromboembolism

- Combined oral contraceptive pill

- Cancer

- Obesity

- Hormone replacement therapy

Diagram - Virchow's Triad: the relationship between endothelial injury, hypercoagulability, and venous stasis

Creative commons source by Dr.Vijaya chandar, MBBS [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

The above risk factors can be divided into those that are;

- Temporary; for example, pregnancy, the pill, and immobilisation.

- Permanent; for example, cancer.

It is thought that 50% of patients with a PE have a temporary risk factor and that 25% have a permanent, but that 25% don’t have any risk factors at all. It is important to realise that prevention of a PE, for example through the use of compression stockings on a long haul flight, is extremely important, and more easily implemented than treatment.

If an embolus occludes over 30% of the arterial bed, then pulmonary arterial pressure will increase. This leads to right ventricular dilation (in accordance with the Frank-Starling curve seen in the Cardiovascular unit) and the release of inotropes in order to control the blood pressure. However, the release of inotropes causes pulmonary artery vasoconstriction, thus further exacerbating the original problem. This ‘fault’ in the body’s response to pulmonary artery occlusion is the main cause of death due to PE.

The areas of the lung that used to be perfused by the areas of now-blocked arteries no longer have a blood supply, meaning no gas exchange can take place in these areas, despite the area being well ventilated. This area has now become alveolar dead space, meaning the body will redirect the blood to other areas of the lung to be perfused. If this increased blood flow is not matched by increased ventilation, then pO2 will drop. This drop in O2 leads to hyperventilation, meaning the CO2 is adequately removed from the body. This means the patient will have low pO2 with normal or low pCO2, which can be classified as type 1 respiratory failure.

The part of the lung that is poorly perfused may undergo infarction, however, this is rare as the bronchial arteries will normally supply the tissue with adequate oxygen. If this does happen then the patient may present with haemoptysis and pleuritic chest pain.

1/3 of patients with a PE have a patent foramen ovale, a hole between the left and right atria which is normal in the fetus but has not closed properly during infancy. Due to the shunting of blood through the foramen, these patients are at risk of having a paradoxical embolism and stroke, because the clot formed in the venous system can pass through the right side of the heart, into the left side of the heart and be pumped through the aorta to the brain (stroke) or another site (paradoxical embolism).

Symptoms of a PE include:

- Shortness of breath

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Cough

- Substernal chest pain

- Fever

- Haemoptysis

- Syncope

- Unilateral leg pain (DVT)

Signs of a PE include:

- Dyspnoea

- Tachycardia

- Low BP

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Pleural rub in cases of pulmonary infarction

- Evidence of DVT, e.g. erythema, increased temperature and tenderness on palpation of the leg

The main differential diagnoses for a pulmonary embolism are pneumothorax, pneumonia, musculoskeletal chest pain, and myocardial infarction.

Patients with a suspected PE should undergo a series of investigations:

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) – would show respiratory alkalosis due to the patient hyperventilating.

- Chest X-ray – to exclude differentials such as pneumothorax or pleural effusion.

- ECG:

- The most common sign of a PE on an ECG is sinus tachycardia.

- This could show an S1Q3T3 pattern; a large S wave in lead I, and a Q wave with an inverted T wave in lead III, which are all classic signs of right heart strain. This is a common textbook presentation but is not actually common in clinical practice.

- There could also be no signs on ECG – a normal ECG cannot rule out a PE.

- D-dimers:

- Measured in a blood test, d-dimer is a fibrin degradation product released into the blood when a thrombus is degraded by fibrinolysis.

- In a patient with a low likelihood of PE, a normal d-dimer can rule a PE out. However, if the patient has a high probability of PE a normal D-dimer should not be used to rule a PE out, as its negative predictive value is too low to use.

- This means that if a PE is likely, a D-dimer is not a useful investigation, because it cannot be used to rule in or out a PE, and so a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) should be done immediately.

- A Wells Score should be calculated for any patient where a PE is a possible cause of symptoms. The components of a Wells Score are:

- Clinical Signs or Symptoms of a DVT – 3 points

- PE is the most likely clinical diagnosis – 3 points

- Heart rate >100 bpm – 1.5 points

- The patient has been immobilised for more than 3 days or has had surgery in the past 4 weeks – 1.5 points

- Previous PE or DVT – 1.5 points

- Haemoptysis – 1 point

- Malignancy with treatment within the past 6 months or active palliative malignancy –1 point

- A score of >4 indicates a PE is likely

- A score of <= 4 indicates a PE is unlikely

- Imaging:

- CT Pulmonary Angiogram (CTPA)

- Ventilation Perfusion Lung Scintigraphy (VQ scan)

Pulmonary emboli can be imaged through the use of a CT pulmonary angiogram or ventilation-perfusion lung scintigraphy (usually if CTPA is not available or a patient is pregnant). These should be used in conjunction with a convincing history.

A patient with a suspected PE should be given O2 immediately to increase pO2, and immediate heparinisation or direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) administration, which reduces mortality by preventing the thrombus from propagating in the pulmonary artery and allowing the body’s fibrinolytic system to lyse the thrombus. It reduces the frequency of further embolism but doesn’t dissolve the clot already present.

Patients with a high risk of PE should also be given haemodynamic support, respiratory support, and exogenous fibrinolytics (given via percutaneous catheter into the pulmonary arteries). Procedures used to remove the embolus include percutaneous catheter directed thrombectomy, or surgical pulmonary embolectomy.

Once patients have had their initial treatment for a PE, they should be started on an oral anticoagulant (e.g. warfarin or a DOAC), for either:

- 3 months if there is an identifiable temporary risk factor that CAUSED the PE, OR

- Indefinitely if there is a permanent or unidentifiable risk factor

Edited by: Dr. Marcus Judge

Reviewed by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

- 4853