Next Lesson - Lung Cancer

Abstract

- A pneumothorax is defined as the presence of air in the pleural space.

- A primary pneumothorax has no obvious cause, whereas a secondary pneumothorax is caused by underlying disease.

- A tension pneumothorax is most commonly caused by trauma, involves high pressures in the pleural space, and is a medical emergency.

- A pleural effusion is defined as a collection of fluid in the pleural space, related to issues the absorption (resulting in a transudate) or production (resulting in an exudate) of pleural fluid.

Core

The pleural space is defined as the potential space between the visceral and parietal pleura. This space contains a very tiny amount of fluid and exists in a state of negative pressure due to the elastic recoil of the lungs opposing the expanding potential of the chest wall. A pneumothorax is defined as the presence of air in the pleural space.

Pneumothoraces can be defined by their cause:

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax is, as the name suggests, a pneumothorax that occurs seemingly spontaneously, and not due to any underling pulmonary pathology. They most commonly occur in young, tall, thin males, with no predisposing lung disease or history of trauma. It isn’t fully understood how primary spontaneous pneumothoraces occur, but the most common line of thinking is that some people have small blebs (bubble-like structures) on the lung surface which can rupture due to microtrauma, for example in exercise.

A secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs again spontaneously, but as a consequence of pathology. This can be due to either an underling lung problem, most commonly COPD or asthma, or due to trauma, such as a fractured rib or severe blunt chest trauma. The cause could also be iatrogenic, for example from the insertion of a central venous line, or fine needle aspiration in the breast.

A tension pneumothorax occurs when a one-way valve system is created at the place where the pleural membrane has been breached, meaning that air can enter the pleural space on inspiration, but can’t leave during expiration, as the change in pressure causes the newly created valve to close.

This means that there is an increase in intrapleural pressure, to the point where it exceeds atmospheric pressure, and starts to collapse the lung. This is a medical emergency because no air can be moved in or out of the lungs.

A person with a pneumothorax will typically present with a sudden onset of pleuritic chest pain (pleuritic chest pain will be exacerbated by deep breathing, sneezing, or coughing), a cough and breathlessness.

On examination the patient will be dyspnoeic, tachycardic, hypotensive (if the pneumothorax is severe), with reduced chest movements, hyper-resonance on percussion and reduced breath sounds on auscultation. These signs will be found on the affected side.

Additional signs and symptoms suggesting a tension pneumothorax include severe respiratory destress, tracheal deviation away from the pneumothorax, fatigue, a raised JVP (jugular venous pressure) and hypotension. These need to be checked for in any case of suspected pneumothorax because a tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency.

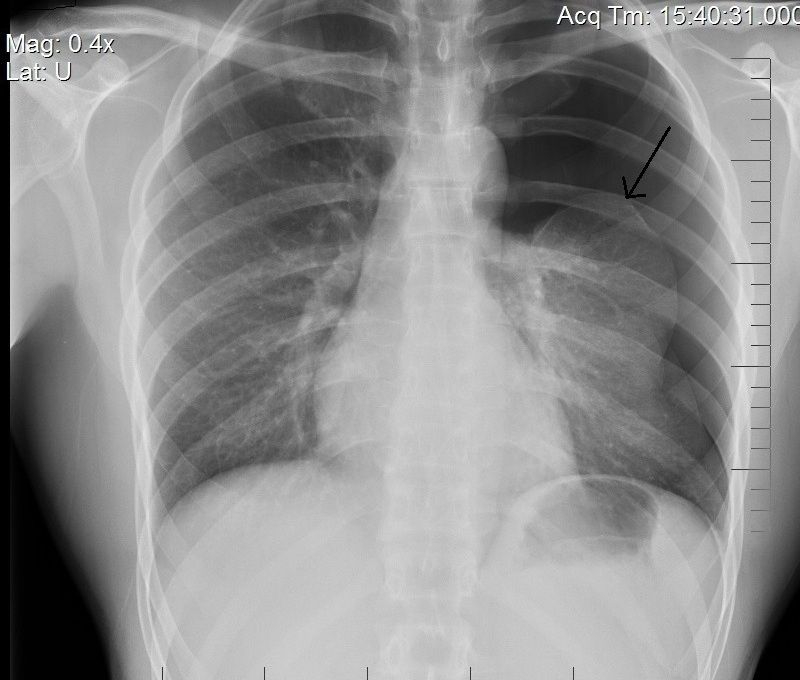

Diagnosis of a pneumothorax is done via a chest x-ray, which will show an area without lung markings, where the lung is usually seen. In tension pneumothorax tracheal deviation will also be seen.

Image - A chest radiograph showing a left-sided pneumothorax, which can be seen by the absent lung markings in the left lung field. The arrow points to the outer edge of the collapsed left lung

Public Domain Source by Mynameisderek [Public domain]

The definitive management of a pneumothorax is via insertion of a chest drain. For a spontaneous pneumothorax, the drain should be inserted in the fifth intercostal space at the mid-axillary line.

In comparison, a tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency and should be treated as soon as possible with the insertion of a wide-bore cannula in the second intercostal space, mid-clavicular line until a chest drain can be inserted.

A pleural effusion is defined as a collection of fluid in the pleural space, which is caused by either a problem with the absorption (resulting in a transudate) or production (resulting in an exudate) of pleural fluid.

The difference between a transudate and exudate can be investigated through measurement of the protein content of the fluid.

A transudate can be detected by its low protein content (<30g/L), and causes of transudate include: congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome and liver cirrhosis. All of these conditions cause an increase in hydrostatic pressure of the blood.

An exudate, in comparison, has a high protein content, with causes including malignancy, infection and pulmonary embolism.

Light’s criteria can also be used to determine if a fluid is exudate, if any of the following are present:

- Serum protein > 0.5 g/L

- Serum LDH > 0.6 g/L

It can also be useful to remember that bilateral effusions are more likely to have a transudative cause (as the reduced hydrostatic pressure is a circulation wide problem, affecting both lungs) and unilateral effusions are more likely to have an exudative cause (because malignancy, PE and infection are likely to occur on one side only). However, this isn’t always the case, and should only be used as a very rough guide.

Symptoms of pleural effusion usually come on gradually, and include breathlessness, chest pain, a cough and symptoms of the underlying cause.

On examination, there may be ‘stony dullness’ on percussion, reduced breath sounds, reduced vocal resonance over the effusion, reduced lung expansion, and in large effusion tracheal deviation away from the site of the effusion. ‘Stony dullness’ on percussion is pathognomonic for pleural effusion.

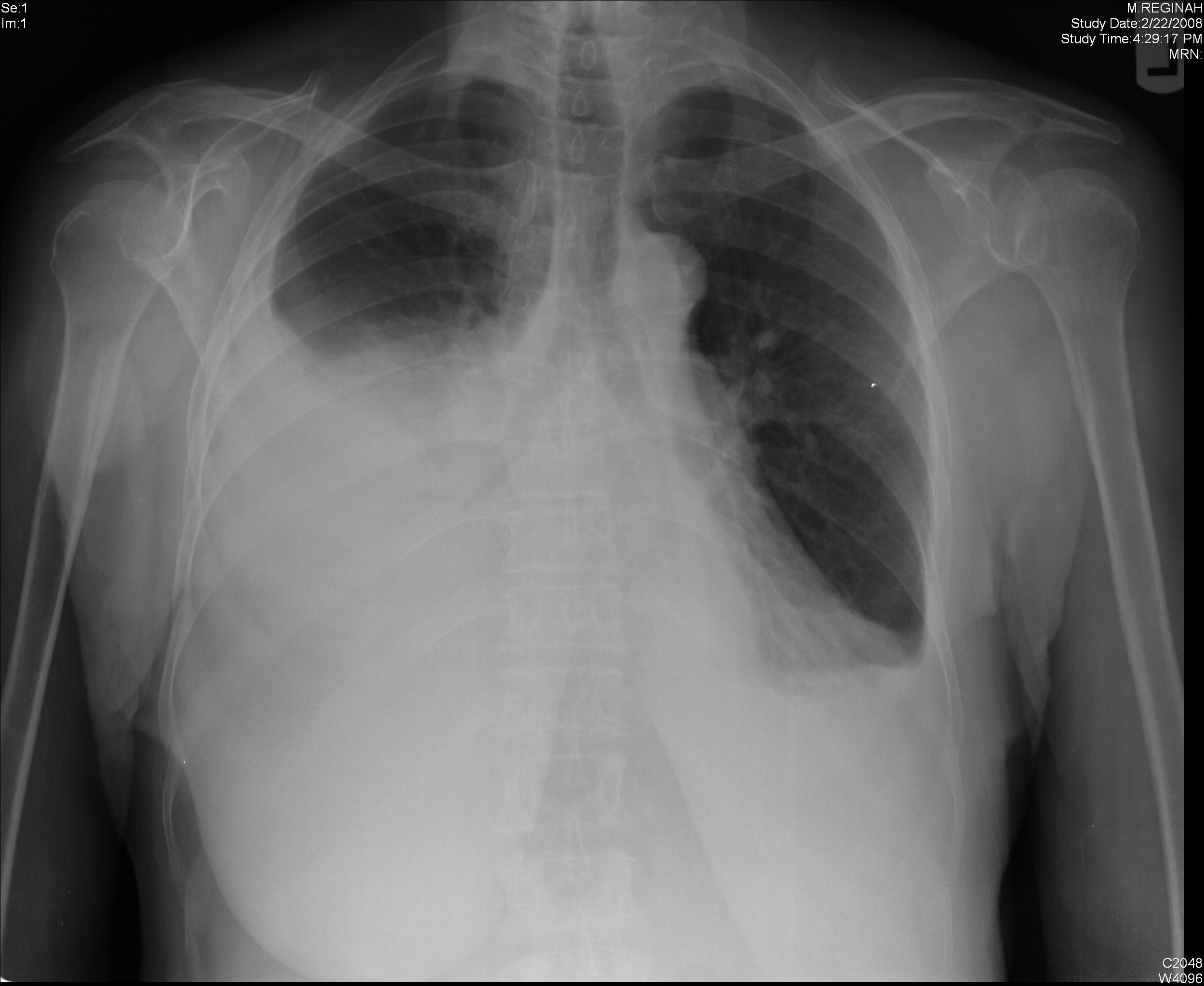

Pleural effusions can be imaged using a chest x-ray, which will show blunting of the costophrenic and cardiophrenic angles, and a meniscal line where the fluid ends.

Ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration can also be performed in order to determine whether the effusion is transudative or exudative. It is important to determine the cause of an exudate before the effusion is treated, as removing the effusion may hide an underlying malignancy, and without management of the cause, the effusion is likely to recur.

Large pleural effusions can be managed via insertion of a chest drain, but definitive management is through treating the underlying cause.

Image - A chest radiograph showing a right-sided pleural effusion. The cardiophrenic and costophrenic angles are completely lost, and a menisci can be seen at the superior margin of the effusion

Creative commons source by Yale Rosen [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Edited by: Dr. Maddie Swannack

Reviewed by: Dr. Thomas Burnell

- 13184